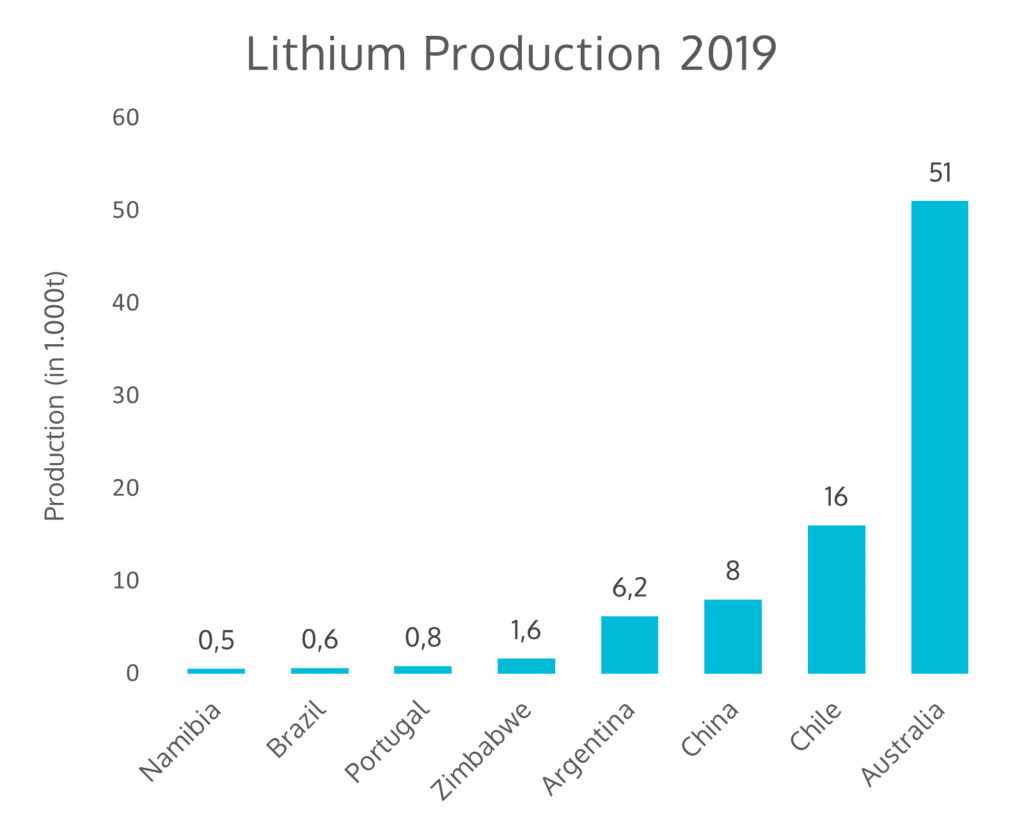

Today, over 90% of the world’s supply of lithium comes from Australia, Chile, Argentina, and China. Conventional lithium mining raises many environmental and ethical concerns, especially regarding the high water consumption in South America. As a result, automakers are seeking to diversify their supply chains of one of the most important elements in battery production. Could locally sourced lithium be a good alternative? This article gives an overview of European reserves, highlights different lithium mining projects, and discusses the benefits and concerns they entail.

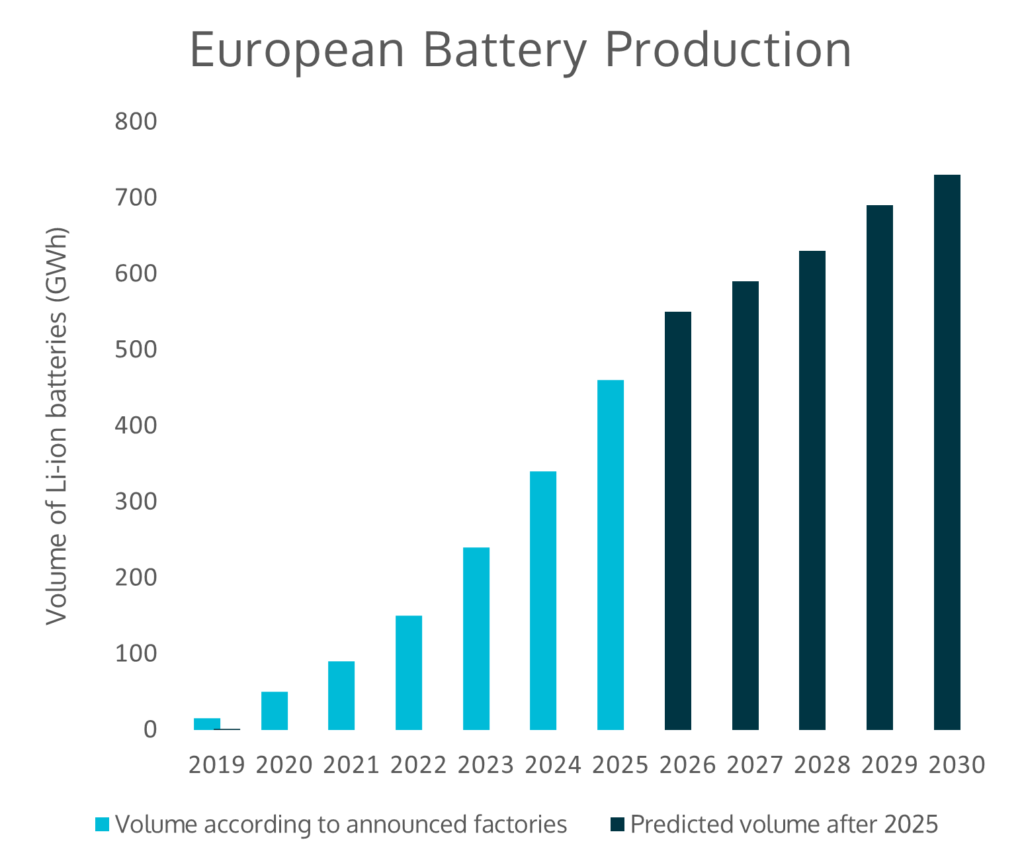

Europe is trying to become more independent from countries like China and the US for its transformation towards a more sustainable future. 22 Gigafactories will open their gates on the continent in the near future. This means that European demand for lithium will skyrocket, even though modern batteries require less and less lithium.

Where Does Lithium Come From Today?

Electrification is a crucial step towards the reduction of carbon emissions. However, the way of sourcing raw materials for batteries poses some problems: At the moment, most of the world’s supply is coming from Australia, China, and South America, where extraction and processing take a huge toll on the environment and water supply. Most of the raw material is shipped to China, where it is processed in an energy-intensive way, usually using fossil fuels. The transport routes add to the environmental impact.

In the South American salars (salt flats), saltwater containing lithium is brought to the surface from underground lakes and evaporated in large basins. In Australia and Europe, lithium is mostly extracted from spodumene ore. In both cases, the raw material is further processed into battery-grade lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide.

If you’re interested in the different ways of extracting and processing lithium and which role mining plays in clean energy transitions, take a look at this report (page 138ff) from the International Energy Agency. It also explains the difference between the compounds of lithium mentioned in this post, quantifies the environmental impact of conventional lithium extraction, and addresses the ethical problems related to labor violations.

Europe’s Role in the Value Chain

“We import lithium for electric cars, platinum to produce clean hydrogen, silicon metal for solar panels. 98% of the rare earth elements we need come from a single supplier: China. This is not sustainable. So we must diversify our supply chains.”

Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission

For that reason, the European Commission is funding the European Raw Materials Alliance, which aims to establish the entire value chain of batteries in Europe. Battery materials are also to be sourced from Europe. One big part of the transition will be to recycle batteries and reuse the extracted materials. However, at the moment there are virtually no spent batteries to recycle, under 2 GWh/year worldwide. This supply could increase by a factor of up to 50 by 2030 and even by 650 by 2040. As of today, recycling material is much more expensive than mining. Companies like VW and BASF want to change that, one of my upcoming articles will feature these different recycling efforts.

Until we have a large supply of spent batteries, batteries will be manufactured from sourced material. One option is mining local lithium and thus becoming independent of foreign suppliers. But does Europe even have enough lithium?

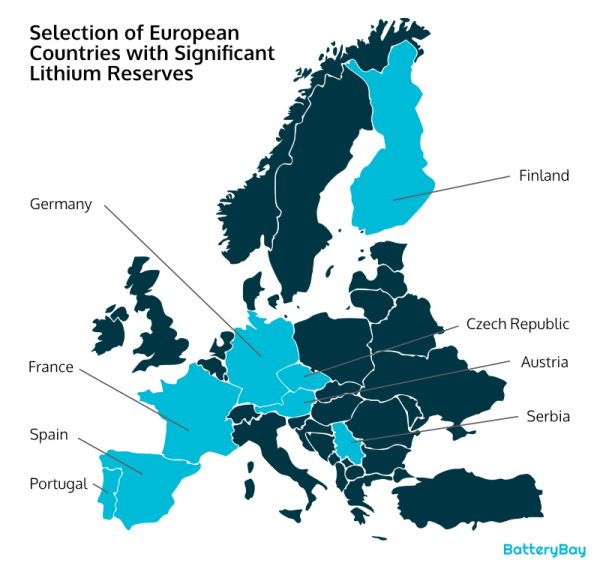

Although countries such as Chile, Australia, and Argentina hold the largest deposits, the element is also present in Europe. In recent years, lithium has been detected at many sites and could be mined soon.

Portugal and Spain

Portugal has one of the most promising lithium reserves in Europe. The United States Geological Survey estimates it at around 60.000 tonnes (pure lithium equivalent). At the moment around 900 tonnes are extracted every year (2020). 11 sites have the potential to be part of the European supply chain. One of the most promising sites though, Covas de Barroso, has been vehemently rejected by local residents who fear the destruction of the countryside, declared a world heritage site for agriculture, by the environmentally harmful open-cast mines.

The mine would bring an economic upswing to the region and make the country a big player in supplying the European energy transition. However, all stakeholders have to be taken into account when planning a project with that much of an impact on nature. British mining company Savannah recently moved closer to actually mining in Portugal when they received preliminary approval based on their environmental impact study. The next step will be public consultation.

On the other side of the border, in Extremadura, Spain, the lithium reserves go on. Infinity Lithium wants to dig up an open-cast mine and expects to be able to produce around 15.000 tonnes of battery-grade lithium hydroxide per year. The mine and production plant would create 1.000 jobs in one of the poorest regions of Spain. However, this project also faces strong opposition from local residents who fear the destruction of this popular recreational area by a hole up to 800m wide and several hundred meters deep. At the moment, however, Portugal seems to be much closer to actually mining and exporting lithium at scale.

The sites could supply battery plants in Spain. VW Group brand Seat wants to build a plant in Barcelona. On Power Day, Volkswagen previously announced it would set up one of six battery factories either in France or Spain. Nissan also considered converting an existing plant in the area for the production of batteries.

Serbia

Serbia also sits on one of the biggest reserves of lithium in Europe. British-Australian company Rio Tinto has already heavily invested in different mines and tested the soil for its concentration of the metal. In February 2021, the Serbian prime minister Ana Brnabic declared that the export of lithium as a raw material would be prohibited. That way, the baltic state strives to become a European hub for the production of batteries, electric cars, and other products containing lithium. This could entail a big upswing for the economy.

Rio Tinto plans to start operations at the Jadar mine in 2023. Serbia is estimated to sit on 118 million tons of ore containing 1.8 percent lithium oxide. Rio Tinto estimates around 55,000 tonnes of battery-grade lithium carbonate could be produced per year. However, environmental issues and a lack of transparency e.g. about the amount of lithium at the mining sites (the estimates range from 1.4% to 10% of the world reserves) have raised doubts about the project’s feasibility. Also, there are protests against the construction of a mining and processing facility. Rio Tinto has already been accused of causing major environmental disruption by disregarding regulation at other mining sites.

Finland

Aside from cobalt, Finland could also export lithium in the future. In Kaustinen, like at other European sites, lithium is found in bedrock. One Finnish company, Keliber, plans on mining at that site and constructing a refinery to produce battery-grade lithium hydroxide. Construction is supposed to begin in the summer of 2022, operations in 2024.

The company wants to produce 15,000 tonnes of lithium hydroxide per year. It prides itself on delivering a product with a lower carbon footprint by shortening transport routes. For example, Northvolt’s Gigafactory for battery production is less than 400 km from the Finnish mining site. Keliber has recently received funding notification as part of IPCEI.

Another site in Finland could prove to be profitable in the future. Canadian United Lithium recently announced it wants to acquire Kietyönmäki, a lithium prospect discovered in the 1980s. However, it is unclear how much lithium the soil at this site holds in total or whether it will be mined. The company is also planning a second project in Sweden, where test drillings will show the potential of the site. The site is less than 600 km from Northvolt Ett.

German-Czech Border

In the German-Czech region of Cínovec / Zinnwald, developments for the extraction of lithium have been going forward. They are supported by local authorities. On the German side, where around 1/3 of the reserves are situated, lithium could be mined with comparatively little destruction of the environment. Lithium has been detected in a former tin mine that was abandoned in the 1990s, which had caused a large outflow from the region. The mayor of Altenberg expects many jobs and an economic upswing through the cooperation with Deutsche Lithium GmbH.

The company’s CEO, Armin Müller, thinks that the German mining site contains around 125,000 tons of lithium, enough to produce around 660,000 tons of battery-grade lithium carbonate. That is enough for up to 20 M mid-sized electric cars. Altenberg is around 2 hours from Berlin, where construction for Tesla’s battery Gigafactory could soon begin, and only around one hour from Schwarzheide, where BASF is currently constructing its cathode plant. The future VW plant in Salzgitter is also not far away. This could prove to be a good locational advantage for the mine.

Austria

In 2017, things looked good for Austria to become a supplier for European electromobility. However, the project of the Australian company European Lithium is currently in limbo. Because of funding issues and environmental concerns from local residents, as well as some disputes, the future of the project is unclear at the moment.

The community of Wolfsberg in southern Austria sits on a reserve of lithium-rich rock. Up to 10,000 tonnes of battery-grade lithium hydroxide could be produced at the local plant each year. The feasibility study of the company European Lithium, originally planned for 2019, will be carried out this year, and lithium mining will not begin before the end of 2022/beginning of 2023, CEO Dietrich Wanke said. The coming years will show whether this mine will make Austria a player in the European battery supply chain.

Other Methods of Extraction: Upper Rhine Valley

A different approach to extracting lithium without a big environmental impact has recently been presented in the German newspaper Handelsblatt: In the Franco-German region of the Upper-Rhine Valley, thermal water has been used for heat and power generation for years. Now the startup Vulcan Energy wants to extract lithium from that mineral-rich water.

The first pilot plant is to be in place by the end of the year. If successful, extraction could start in 2024. The company wants to work its way up from 15,000 tonnes of lithium hydroxide per year to 25,000 tonnes per year. However, they’ll need €700 M in funding in the first stage and an additional €400 M in the second stage. With geothermal energy, Vulcan Energy expects to extract lithium in a carbon-neutral way.

The German legislator just presented a new law draft to facilitate the approval of new lithium projects. For lithium ore, property lines make the legal situation clear. Lithium salts dissolved water that extends over many properties raise the question of ownership. This new law would declare the different forms of lithium “free to mine“. That way, companies could extract lithium from the aqueous solution from large areas of land below several properties.

On the French side of the border, EuGeLi, a project started in 2019 has an estimated annual production capacity of 1,500 tonnes of lithium carbonate, which is around 10% of the French demand. The project is a collaborative research effort supported or advised by companies like BASF, PSA Groupe (Citroën, Opel, Peugeot), Electricité de Strasbourg-Géothermie, and EDF (the second-largest power company in the world) and partially funded by EIT RawMaterials, leader of the European Raw Materials Alliance.

This is a non-exhaustive list of countries with lithium reserves, there might be other projects. I am aware of some lithium mining projects in Ukraine. Let me know about any other noteworthy initiatives.

Why Aren’t We Mining Yet?

The majority of the world’s lithium lies below the surface of China, Australia, Chile, and Argentina. However, the mentioned examples above show that there are lithium reserves on the European continent that could potentially be extracted for battery production. How extensive these reserves are and how much of them are usable is unclear. The deviating statements, for example on the amount of lithium available in Serbia, show that these companies’ claims have to be taken with a grain of salt.

There are environmental downsides that can’t be disregarded. All of the stakeholder’s viewpoints have to be taken into account when planning the extraction at a particular site. It must be assessed at every single site whether the benefit of the mined lithium for electrification is worth the local environmental disruption.

At the moment, European lithium is not extracted at scale and the following years will show whether the promises of the mining companies prove to be true. The difficulty to mine and process battery-grade lithium is an obstacle to this shift in the supply chain. Mining and processing are still comparatively expensive in Europe. The competitiveness will therefore also depend on the development of the global market price.

The Case For European Lithium

Local lithium sourcing can make Europe much more independent from countries like China. The goal in building more than 20 battery plants in Europe is to lower the dependency on overseas suppliers, which can only be reached when the entire value chain is transformed or at least more diversified.

European environmental regulation is much stricter than those e.g. in South America. While the environmental impact of lithium extraction can’t be evaded (there’s no such thing as “green mining”), it can be mitigated. Cutting transport routes and using renewable energy at refineries further reduce the lithium’s environmental impact.

Also, it is easier to assure that human rights are complied with throughout the value chain of electric cars sold in Europe. Germany even implemented a law to assure this adherence to human rights along the supply chain recently. Locally sourced lithium could facilitate abiding by the so-called “Lieferkettengesetz” for battery producers.

In the future, recycled material should make up a big percentage of the lithium and other materials used for the production of new batteries. However, before the necessary capacities are available, an interim solution has to be found as an alternative to the destructive conventional ways of lithium mining.

A Unique Selling Point for European Batteries?

Using fairer, more sustainable, locally sourced lithium in batteries could prove to be a unique selling point for European companies like VW, Renault, or Northvolt, who plans on producing the “greenest battery”. International companies like Tesla have placed their bet on Europe as a big player in battery production. They could also profit from the diversification of the lithium supply chain. On the other hand, the endorsement by big companies could help to make European lithium a reality.

Follow me on Twitter (@BatteryBayEU)! I’m looking forward to learning about your involvement or interest in the industry and chatting about everything batteries.

Also, please feel free to use the comment section below to leave any feedback or suggestions!